Marine Ecology News Digest – November 2025

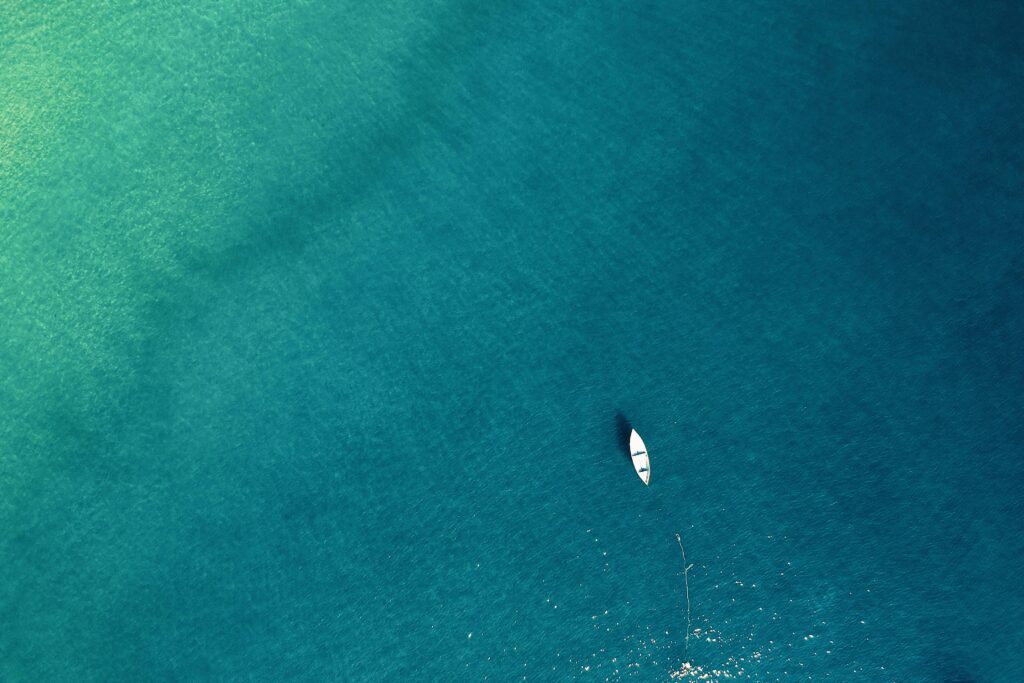

November is not a month that lends itself to optimism or alarm. It sits somewhere in between. The sea grows darker, fieldwork slows, and much of what becomes visible is not new discovery, but consequence. Patterns observed earlier in the year begin to feel more permanent. Temporary explanations wear thin.

This November, marine ecology feels quieter on the surface and heavier underneath. There have been no single moments demanding attention, no dramatic reversals. Instead, the month has been shaped by accumulation — of data, of pressure, and of decisions whose effects are now easier to trace.

What follows is not a catalogue of events, but a reading of the water as it stands.

Storms, Sediment, and the Changing Shape of Coasts

Autumn storms across northern Europe and parts of the North Atlantic have once again highlighted how closely marine ecology is tied to land use. Increased rainfall has driven sediment and nutrient runoff into coastal waters at levels that many monitoring programmes now consider routine rather than exceptional.

In estuaries and nearshore habitats, turbidity spikes recorded this November were not remarkable for their height, but for their duration. Sediment stayed suspended longer. Light penetration dropped for days rather than hours. For seagrass beds and benthic algae, this matters.

Researchers working in sheltered bays along the UK coast have noted that even short-lived storms now have outsized ecological effects because baseline conditions are already strained. When systems operate close to their limits, recovery windows shrink.

This is not a failure of storm management, but a reminder that climate-driven changes amplify existing weaknesses. Catchment practices upstream continue to shape marine outcomes downstream, often invisibly.

Cold-Water Species Under Quiet Pressure

As surface waters cool, attention often drifts away from temperature stress. November’s data suggests this may be misleading. Several cold-adapted species — including certain echinoderms and bivalves — are showing signs of long-term stress not from heat itself, but from variability.

Temperature swings, rather than absolute highs, are increasingly implicated in reduced growth and altered reproductive timing. In the North Sea and parts of the Baltic, monitoring indicates that spawning periods are becoming less predictable, complicating both ecological interactions and fisheries planning.

These changes rarely make headlines. They do not resemble collapse. Yet they erode stability in ways that only become visible years later, when recruitment fails to meet expectations for reasons no single factor can fully explain.

November has reinforced a familiar but uncomfortable lesson: ecosystems tend to fray before they break.

Offshore Energy and Ecological Negotiation

This month has also seen renewed discussion around offshore wind and marine spatial planning. As projects move from proposal to operation, ecological impacts are shifting from hypothetical to measurable.

Recent monitoring around established wind farms suggests a mixed picture. In some locations, turbine foundations are acting as artificial reefs, attracting fish and invertebrates. In others, changes in sediment movement and noise exposure appear to be affecting sensitive species, particularly during construction and maintenance phases.

What is different now is the tone of discussion. Developers, regulators, and ecologists are increasingly speaking the same language — not always agreeing, but engaging earlier and with clearer expectations. Adaptive management plans, once treated as paperwork exercises, are being tested in real time.

November’s takeaway is not that offshore energy is benign or harmful, but that ecological outcomes depend heavily on design choices made long before turbines appear on the horizon.

Marine Protected Areas: The Long View Begins to Matter

With fewer new MPAs announced this month, attention has shifted to those established a decade or more ago. Long-term datasets are now long enough to say something meaningful — and the results are uneven.

In well-enforced MPAs, species diversity and biomass continue to outperform surrounding areas. In poorly enforced ones, differences are negligible. This is not a new finding, but November has brought more candour in how it is discussed.

Several reviews published this month emphasise governance over geography. Protection works where rules are clear, enforced, and socially accepted. Where MPAs exist primarily to meet coverage targets, ecological benefits remain thin.

Encouragingly, some agencies are beginning to reassess underperforming MPAs rather than simply adding new ones. It is a quieter kind of progress, but arguably a more honest one.

Microplastics and the Problem of Normalisation

Plastic pollution has reached an awkward stage in public discourse. Everyone knows it exists. Fewer people feel shocked by it. November’s research has not changed that, but it has sharpened understanding of exposure pathways.

Studies published this month reinforce the role of atmospheric transport in distributing microplastics far from their original sources. Fibres detected in offshore waters increasingly resemble those found in urban air samples, blurring the boundary between marine and terrestrial pollution.

For marine organisms, this means exposure is not confined to feeding behaviour. Filtration, respiration, and surface contact all play roles. The ecological implications remain complex and difficult to isolate.

The danger, as several researchers have noted, is not ignorance but fatigue. When a problem becomes normalised, urgency fades. November’s findings offer clarity, but whether they translate into action remains uncertain.

Fisheries at the Edge of Predictability

November assessments of several commercial stocks suggest that variability, rather than decline, is becoming the dominant management challenge. Shifting distributions, altered migration timing, and inconsistent recruitment are complicating models built on historical patterns.

Fish are still present, but not always where or when they are expected. For fishing communities, this creates economic uncertainty even in the absence of clear ecological collapse.

Some regions are responding with more flexible management tools, including dynamic closures and seasonal adjustments informed by real-time data. These approaches are resource-intensive but increasingly necessary.

The month’s discussions point toward a future where fisheries management resembles navigation more than control — constant course correction rather than fixed routes.

Coastal Communities and Uneven Capacity

November has also brought renewed focus on the social side of marine ecology. From flood defence planning to shellfish harvesting, coastal communities continue to sit at the interface between ecological change and economic reality.

In parts of northern Europe, nature-based solutions such as saltmarsh restoration are becoming mainstream. Elsewhere, particularly in lower-income regions, communities face rising risks with limited support.

The disparity is not new, but it is becoming harder to ignore. Several international reports released this month emphasise that ecological resilience cannot be separated from governance, finance, and local knowledge.

Marine ecology, it seems, is increasingly about who has the capacity to adapt, not just what needs adapting.

A Month Without Illusions

November 2025 has not offered clarity in the form of solutions. Instead, it has provided sharper questions. How long can systems absorb variability before stability gives way? How much intervention is enough — and how much is too late?

What stands out is not crisis or comfort, but realism. The ocean continues to respond precisely to cumulative pressure and deliberate care. Nothing more. Nothing less.

As the year approaches its close, marine ecology finds itself in a familiar position: armed with better data, clearer understanding, and the same underlying challenge of turning knowledge into restraint.

November does not demand conclusions. It asks for attention.

References

-

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO)

-

International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES)

-

Marine Conservation Society (UK)

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

-

European Environment Agency (EEA)

-

FAO – State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture

-

Peer-reviewed research from Marine Ecology Progress Series, Global Change Biology, Frontiers in Marine Science, and ICES Journal of Marine Science